THE SET-UP: Environmentally speaking, Elon Musk is the meteor. No, I’m not talking about the pollution SpaceX leaves on the ground and in atmosphere … although that is a problem. Oddly enough, I suspect recent attempts to rein-in SpaceX’s pollution contributed to Musk’s transformation into the ideological lovechild of Ayn Rand and Milton Friedman.

Unfortunately, Elon Musk’s environmental impact is not localized to a launch pad or a rocket’s trajectory. Instead, his widespread cull of the Federal workforce has hit everywhere and touched everything all at once. Behind far more visible stories about crippled national parks and the ominous loss of 3,400 Forest Service staffers are numerous agencies you probably never heard of … like the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), which lost 400 skilled employees. As The New York Times noted:

The plant protection and quarantine program within APHIS was especially hard hit, losing more than 200 employees, including agricultural inspectors, entomologists, taxonomists and even tree climbers who surveyed for pests.

Another obscure casualty is the Livestock Behavior Research Unit at Purdue University in Indiana. Sentient Media lamented the effective end of its groundbreaking “study of animal pain, nutrition, cognition and stress in response to the conditions on farms.” Their work translated into “better on-farm animal welfare standards,” among other things. After thirty-three years of work, Musk ended it with a Thanos-like snap of his fingers.

Then there’s the 420 terminated employees at the “already short-staffed US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)” which Vox describes as “the only government agency whose main goal is to conserve animals, ecosystems, and the life-supporting services they provide.”

Therein lies the rub.

Elon Musk isn’t interested in conserving animals, ecosystems, or the life-supporting services they provide. He’s moving fast … toward Mars … and he’s willing to break whatever it takes to get there … including this planet. For him, the Earth is just a launching pad. He sees no intrinsic value in it or its ecosystems. His messianic notion of saving mankind by leaving Earth behind is strikingly similar to the apocalyptic eschatology imbibed by the Evangelicals who’ve made Trump into the manifestation of God’s will. I guess that makes them a match made in Heaven … or on Mars. Back here on Earth, the impact is the same. - jp

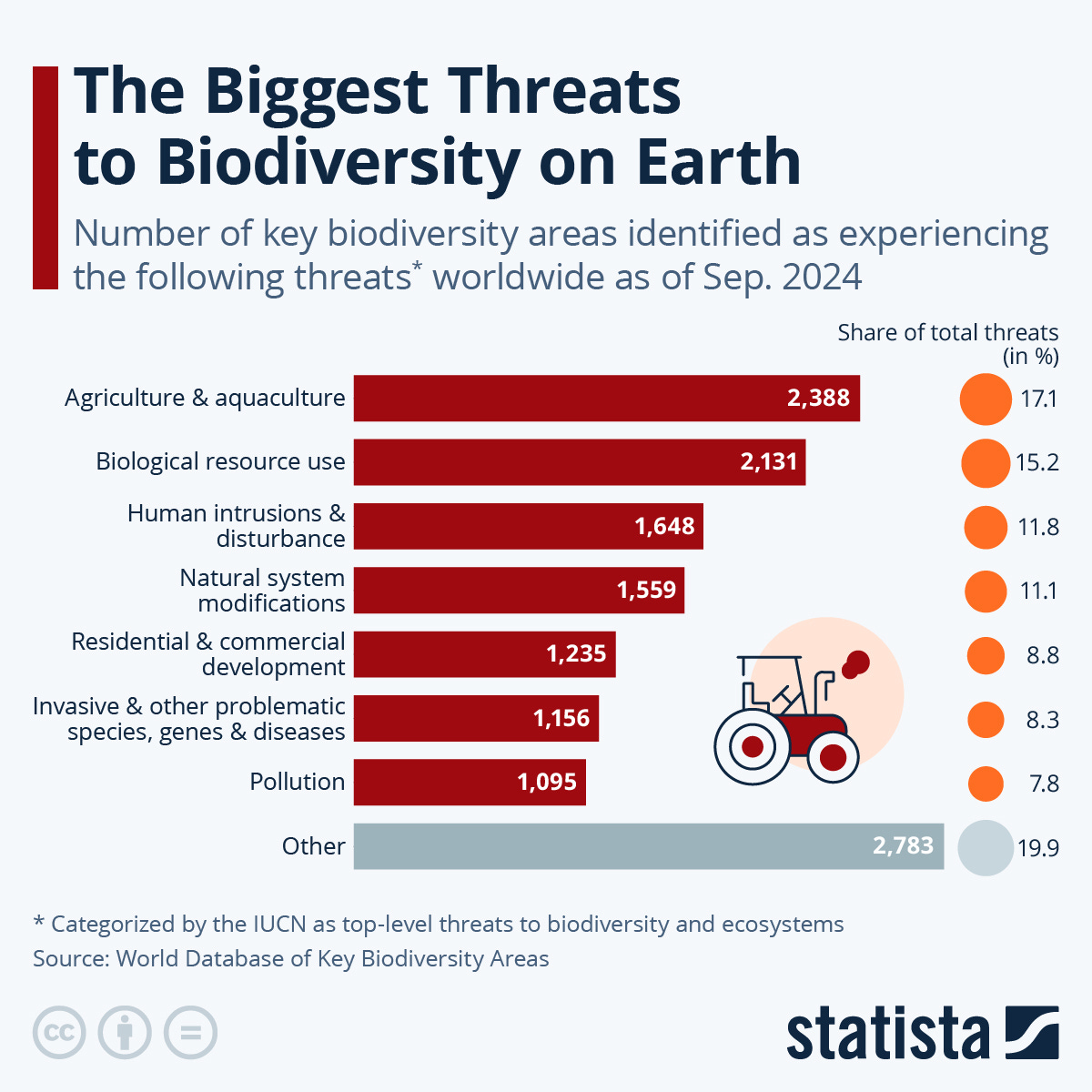

TITLE: The Biggest Threats to Biodiversity on Earth

https://www.statista.com/chart/34006/key-biodiversity-areas-identified-as-experiencing-various-threats/

EXCERPTS: Agriculture and aquaculture are the largest single threat to key biodiversity areas around the world, according to data from the World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas. The categories for the major threats shown on this chart reflect classifications by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which are considered as top-level threats to biodiversity and ecosystems.

As this chart shows, several of the leading threats to biodiversity areas are human-made. For example, the group Human Intrusions and Disturbance encompasses a range of actions from recreational activities to war, civil unrest and military exercises, as well as work activities. Biological resource use includes among other things, hunting as well as logging and wood harvesting. Meanwhile, Natural System Modifications covers activities such as building dams and Pollution spans across threats such as sewage, oil spills, acid rain and noise pollution. The categories of Energy Production and Mining and Transportation and Service Corridors rank in eighth and tenth place, respectively, but have been included in this chart under Other.

TITLE: Who gets the lion's share? Ecologists highlight disparities in global biodiversity conservation funding

https://phys.org/news/2025-02-lion-ecologists-highlight-disparities-global.html

EXCERPTS: The extensive loss of biodiversity represents one of the major crises of our time, threatening not only entire ecosystems but also our current and future livelihoods. As scientists realize the magnitude and scale of ongoing extinctions, it is vital to ascertain the resources available for conservation and whether funds are being effectively distributed to protect species most in need.

A team of researchers from the School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong (HKU), addressed these questions in a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by compiling information on nearly 15,000 funded projects focused on species conservation.

Professor Benoit Guénard, the lead author of the study, noted, "Our first conclusion is that funding for species conservation research remains extremely limited with only US$ 1.93 billion allocated over 25 years to the projects we assessed."

The international conservation funding from 37 governments and NGOs represents a mere 0.3% and 0.01% of the annual budget of the NASA or U.S. military, respectively. This stark comparison underscores the urgent need to dramatically increase such funding to slow global biodiversity loss.

The authors also examined the allocation of this funding to specific species or groups of organisms based on their conservation needs as assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, often called the "barometer of life."

Professor Guénard explains, "Based on previous literature-based studies, we expected biases towards vertebrates and, while this was true, we found the situation much worse than previously estimated. Even within vertebrates, many of the most threatened groups, like amphibians, were largely underfunded with declining funding trends over time."

Another striking example can be found in reptiles, particularly lizards and snakes, where over a thousand species have been identified as threatened, yet 87% of the funding towards reptile conservation is directed towards the seven species of marine turtles.

Professor Guénard states, "This highlights an important mismatch between scientific assessment of conservation and allocation of funding by conservation stakeholders, which appears to rely on the 'charisma' of species. This leads to nearly a third of the funding directed to non-threatened species, while almost 94% of threatened species have not received any support."

Some groups, like plants or insects, received a mere 6% each of the funding despite their vast diversity and the number of threatened species they include, while other major groups, such as fungi or algae, received virtually no funding.

Professor Alice Hughes, a co-author of the study, echoed, "Our traditional view of what is threatened often does not align with species genuinely at threat, leaving many smaller, or 'less charismatic' species neglected. We urgently need to reframe this perspective and better allocate funding across taxa if we want any hope of redressing widespread population declines and the continued loss of biodiversity."

TITLE: Conserving land in wealthy countries may be making things worse somewhere else

https://www.anthropocenemagazine.org/2025/02/conserving-land-in-wealthy-countries-may-be-making-things-worse-somewhere-else/

EXCERPTS: Protecting a piece of land in the U.S. from chainsaws or plows might seem like a win for the environment. But as food and wood crisscross the planet through the arteries of international trade, such conservation measures can, paradoxically, lead to more harm than good.

As nations and conservationists push to protect up to 30% of their land by the end of this decade, scientists are calling attention to this often-overlooked side-effect of well-intentioned efforts. In papers published in mid-February in two of the world’s premier journals, Nature and Science, one group of scientists warned of the potential damage caused by these spillover effects while another team provided a detailed account of how this happens, thanks to our appetite for everything from avocados to vanilla beans.

“Developed nations are essentially exporting extinction,” said David Wilcove, a Princeton University conservation scientist and co-author of the new paper in Nature.

It’s widely recognized that agriculture is a primary driver of the world’s extinction crisis, and that demand in wealthy countries for everything from beef to chocolate to soybeans helps spur deforestation in biodiversity hotspots like Brazil. But measuring the ecological toll of this trade has proven tricky, given the complexity of the global economy. How do you draw a link between a vanilla farm in Madagascar and a bottle of vanilla extract at Whole Foods?

Wilcove and Princeton co-author Alex Wiebe tapped into a series of computer models to illuminate these connections. One computer program described by scientists at Japan’s Research Institute for Humanity and Nature linked money transfers in 15,000 industries spanning 190 countries to deforestation patterns down to the level of a city block, based on satellite images. The Princeton scientists examined how these patterns of deforestation overlapped the habitats of more than 7,000 forest-dwelling birds, mammals and reptiles.

The analysis revealed that goods such as food and timber imported to 24 of the world’s wealthiest countries are responsible for around 13% of the global decline in habitat for those species. Three quarters of those wealthy countries caused more biodiversity losses in other countries than in their own.

The U.S. ranked at the top, with its imports tied to more than double the total international habitat loss compared to second-place Japan. China was nearly tied with its island neighbor. Germany, France and the United Kingdom rounded out the top five. Places that suffered the greatest biodiversity loss due to this trade included parts of Central America and Brazil, southeast Asia, Madagascar and west Africa.

“By increasingly outsourcing their land use, countries have the ability to affect species around the world, even more than within their own borders,” said Wiebe. “This represents a major shift in how new threats to wildlife emerge.”

The research offers a detailed explanation of how national or local conservation measures could worsen biodiversity protections at the global scale. Fencing off potentially productive cropland or forests in wealthier countries that have less biodiversity could simply shift the damage to more ecologically rich places – often tropical countries with fewer environmental safeguards.

“Areas of much greater importance for nature are likely to pay the price for conservation efforts in wealthy nations unless we work to fix this leak,” said Andrew Balmford, a conservation scientist in the University of Cambridge.