TITLE: Why does the US government think a Kroger-Albertsons merger would be bad for grocery shoppers?

https://apnews.com/article/kroger-albertsons-merger-federal-trade-commission-2fda44d9d8b82ef20d6c7e7cffb2ccc3

EXCERPT: “A merger of Kroger and Albertsons would dramatically decrease competition within an already consolidated food retail market, which would result in fewer grocery stores and higher food prices, with predictable adverse consequences for food and nutrition security for consumers across the country,” Peter Lurie, president of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, said in a statement applauding the FTC’s action.

Kroger says no stores would close as a result of the merger. It also promises to invest $1.3 billion to update Albertsons’ existing outlets. But in some places, stores would get sold to a new owner. To stave off monopoly concerns from federal regulators, Kroger and Albertsons agreed to sell 413 stores and eight distribution centers in locations where their operations overlap.

The buyer would be C&S Wholesale Grocers, a grocery supplier that also owns the Piggly Wiggly brand. But the FTC says the divestiture deal is “inadequate” and the proposal doesn’t contain enough stores or other resources to replicate the competition that currently exists between Albertsons and Kroger.

Why do Kroger and Albertsons want to merge?

Kroger and Albertsons agreed to merge in October 2022. The companies said a merger would help them better compete with big retailers like Walmart, Costco and Amazon, which owns Whole Foods, because they would have more power to negotiate prices and could save on distribution and administrative costs. Together, they would control around 13% of the U.S. grocery market; Walmart now controls 22%, while Costco controls 6%, according to J.P. Morgan analyst Ken Goldman.

Why does the Federal Trade Commission oppose the merger?

The FTC says the deal would eliminate the competition that now exists between Kroger and Albertsons, and without competition, buyers would see higher prices, lower quality and fewer shopping choices. In a separate lawsuit filed earlier this month, Colorado’s attorney general gave a specific example. The city of Gunnison, Colorado, has two groceries: Kroger-owned City Market and Albertsons-owned Safeway. The merger would make Kroger the only chain operating in this area, and a Gunnison resident would have to drive 65 miles to a non-Kroger store.

Consumers also would see fewer deals if the stores merged since Kroger and Albertsons currently use promotions to lure shoppers away from the competition, according to the FTC. The agency also foresees less incentive for stores to add or improve services. When Albertsons executives saw unstaffed deli counters at Kroger’s Fred Meyer stores, for example, they added counter staff at their stores. In the same way, Kroger improved its grocery pickup services in some markets to compete with Albertsons.

The FTC says competition at supermarket pharmacy counters also benefits consumers. When Kroger went out-of-network with a major pharmacy benefits administrator last year, for example, Albertsons offered consumers a $75 grocery coupon to transfer their prescriptions.

Would a Kroger and Albertsons definitely result in higher prices?

Kroger says it wouldn’t, and that it would invest $500 million to lower prices across its stores once the deal goes into effect. GlobalData, a market research firm, said discount chains like Aldi and cost-conscious competitors like Walmart would help keep prices in check even if Kroger and Albertsons combined.

But the FTC isn’t convinced. In a 2012 study, FTC economists found that prices increased more than 2% when grocers merged in places where they had little competition. Prices only decreased or stayed the same in markets where grocers had more competitors.

TITLE: Blocking Kroger’s mega-merger with Albertsons won’t save your local grocery store

https://www.cnn.com/2024/02/27/investing/takeaways-supermarket-merger-ftc/index.html

EXCERPT: The FTC said the merger would increase market concentration and hurt competition.

Yet consolidation in the grocery sector is growing, and small grocery stores are struggling.

In 2019, the 20 largest retailers controlled 64% of total food sales, more than double the share from 1990, according to the Agriculture Department.

Traditional grocery stores have also lost ground to Walmart, Costco, dollar stores and online retailers during that span.

The share of spending at traditional supermarkets dropped from 80% in 1990 to 62% in 2012, according to the Agriculture Department.

Independent grocery stores strongly opposed the merger. They argued that the merger would increase the companies’ leverage with merchandise suppliers and leave independent stores unable to stock their own shelves.

“This corporate marriage of two supermarket giants is engineered to enhance the largest conventional grocery chain’s leverage over suppliers at the expense of smaller rivals,” Greg Ferrara, CEO of the National Grocers Association, which represents independent stores and wholesalers, said in a statement.

TITLE: Kroger's “nefarious bargain”

https://popular.info/p/krogers-nefarious-bargain

EXCERPT: In January 2022, as COVID case rates soared nationwide, 8,400 workers at Colorado’s King Soopers supermarkets went on strike for better pay, hours, and on-the-job protections from infection and unruly customers.

King Soopers’ 78 Colorado locations are owned by Kroger, one of the largest grocery firms in the country. The company, which generated $4.3 billion in adjusted operating profit in the year leading up to the strike, called the UFCW’s stoppage “reckless and self-serving.” Workers struck for for 10 days, before ratifying a new contract with higher starting wages and better healthcare benefits in early February 2022.

A lawsuit filed earlier this month by Colorado’s attorney general alleges that Kroger had a secret reason to believe it could weather the UFCW strike two years ago without major disruptions to its King Soopers business: a “nefarious bargain” that it struck with rival grocer Albertsons to ensure the latter wouldn’t poach the struck chain’s picketing workers or inconvenienced customers.

“Executives at the very highest levels of both companies knew of this unlawful arrangement and allowed it to go forward,” the complaint claims, citing contemporaneous emails between the grocers’ executives, as well as subsequent testimony of Albertsons executives before the Federal Trade Commission. The so-called “no-poach” and nonsolicitation agreements “harmed workers and blatantly violated antitrust law,” Colorado A.G. Philip Weiser said in a statement.

The stakes of this suit, filed in U.S. District Court in Denver on February 14th, are dramatic. Less than nine months following the conclusion of the King Soopers strike, Kroger announced a plan to acquire Albertsons for $24.6 billion to create the country’s second-largest mega-grocer behind Walmart. The merger is opposed by a broad coalition of labor organizations, independent industry experts, prominent Congressional Democrats from both chambers, and attorneys general from across the country, including Colorado’s Weiser. Yesterday, the Federal Trade Commission announced its own suit to block the deal.

Blunting labor’s pandemic leverage

Like many businesses with large brick-and-mortar footprints, grocers large and small were desperate to hire employees at the time of the strike, 18 months into the pandemic. By late 2021, shifting labor demand and disproportionate frontline fatalities due to Covid helped push the average hourly wage for restaurant and grocery workers past the $15 mark for the first time.

For Kroger workers, the unusual hiring dynamics offered a particular boon. An Economic Roundtable study of 10,000 of the firm’s workers, underwritten by UFCW and published in January 2022, found that "over three-quarters of Kroger workers are food insecure.” The Executive Excesses 2022 report from the Institute for Policy Studies, a progressive think tank, pegged the median pay of Kroger’s workers nationally at just $26,763 in 2021 — 679 times less than the $18 million Kroger chief executive officer Rodney McMullen was paid that year.

As the hours ticked down towards the King Soopers strike, Denver’s CBS4 reported King Soopers stores were already short 2,400 employees in Colorado. “We have brought in 300, 400 people from across the country from some of our sister companies in Kroger,” division president Joe Kelley told the outlet, describing the grocer’s strike preparations. “We have also been hiring temp workers the best we could. You know what the work market looks like.”

The soaring demand for supposedly “unskilled” labor could have created a rare win-win scenario for Colorado King Soopers workers. A strike to force Kroger to offer UFCW Local 7 a better contract would also invite staff-starved competitors like Albertsons — which unlike Kroger, had agreed to extend negotiations between the union and its 100 Safeway stores in Colorado — to lure picketing workers with higher pay and benefits.

Because Albertsons would continue bargaining with UFCW Local 7 for a Safeway contract while Kroger faced a strike over its offer to King Soopers workers, the union was in a position to play the grocers against one another to improve collective bargaining agreements for both workforces. Such a bidding war over labor was in neither company's interest.

A “nefarious bargain”

To protect King Soopers from an Albertsons recruitment raid, and “help Kroger hold the line” and “stay strong” against the UFCW to prevent a bidding war, Weiser alleges that Albersons’ Denver division president Todd Broderick and senior vice president of labor relations Daniel Dosenbach promised Kroger’s vice president of labor relations Jon McPherson that his firm would not poach workers for the duration of the strike.

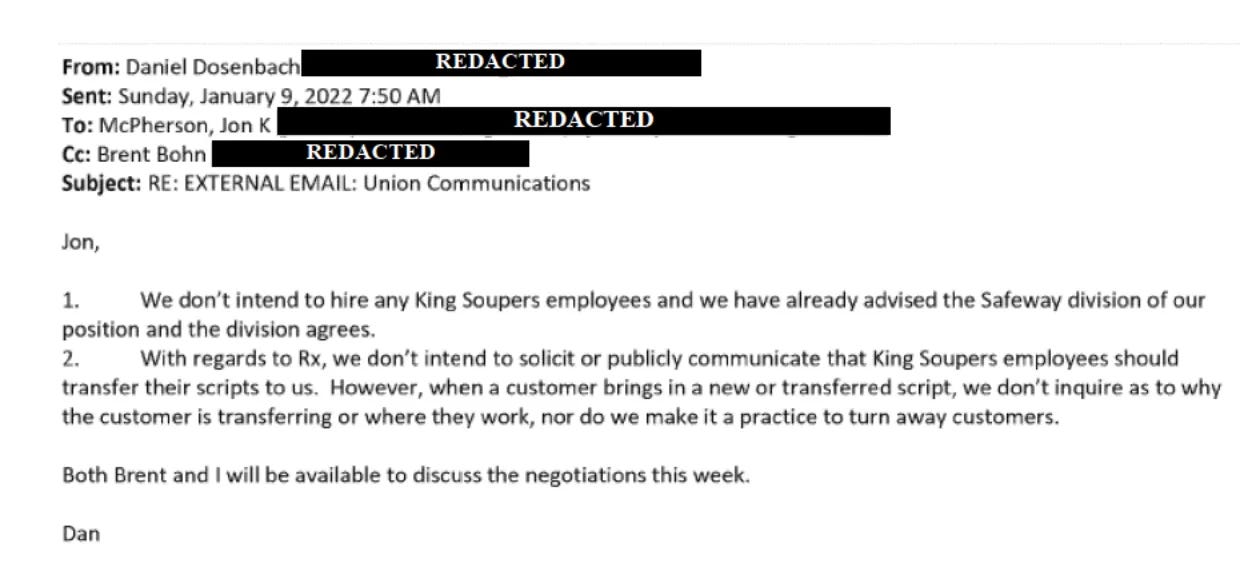

The pair also agreed that Safeway would not encourage King Soopers’ pharmacy customers to move their prescriptions. (For big grocers, pharmacy departments are key because they create customer loyalty and cross-selling opportunities, and King Soopers’ pharmacy technicians were involved in the strike.) Then, they allegedly looped in their respective firms’ top executives about it. The complaint includes a lightly redacted email from Dosenbach to McPherson on January 9th, 2022, with the subject line “Union Communications,” outlining the truce:

A Kroger spokesperson denied the existence of any such arrangements in an emailed statement to Popular Information, calling it “disheartening for Coloradans that General Weiser would mischaracterize the facts.” They declined to elaborate. Albertsons, which reached its own deal with UFCW Local 7 covering 5,400 workers in Colorado and Wyoming in late February 2022, did not respond to Popular Information’s requests for comment.

“The public has a right to know that the leaders of these companies cannot be trusted to do right by their employees or customers,” said Kim Cordova, President of UFCW Local 7 in a statement. A day after the State of Colorado filed suit, the union lodged unfair labor practice charges with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) based on the allegations in the suit. The NLRB complaint accuses both Albertsons and Kroger of violating federal labor laws with “bad-faith bargaining” and “coercive actions.”